I. The 500-page problem: a story of confident failure

Anya is a founding engineer at a bank rolling out an internal compliance copilot, and she is having a bad Tuesday.

A critical regulatory update has landed on her desk: hundreds of pages long, dense with cross-references, and riddled with the kind of “unless…” clauses that keep compliance lawyers employed. Her deadline is tomorrow. So she does the obvious thing, feeds the entire document to a modern LLM with a vast context window, and asks a question that should be simple:

“Do we have new reporting requirements for mid-sized firms using third-party payment processors?”

The model answers in seconds. It is articulate. It cites sections by number. It sounds, frankly, like it knows exactly what it is talking about.

And it is wrong.

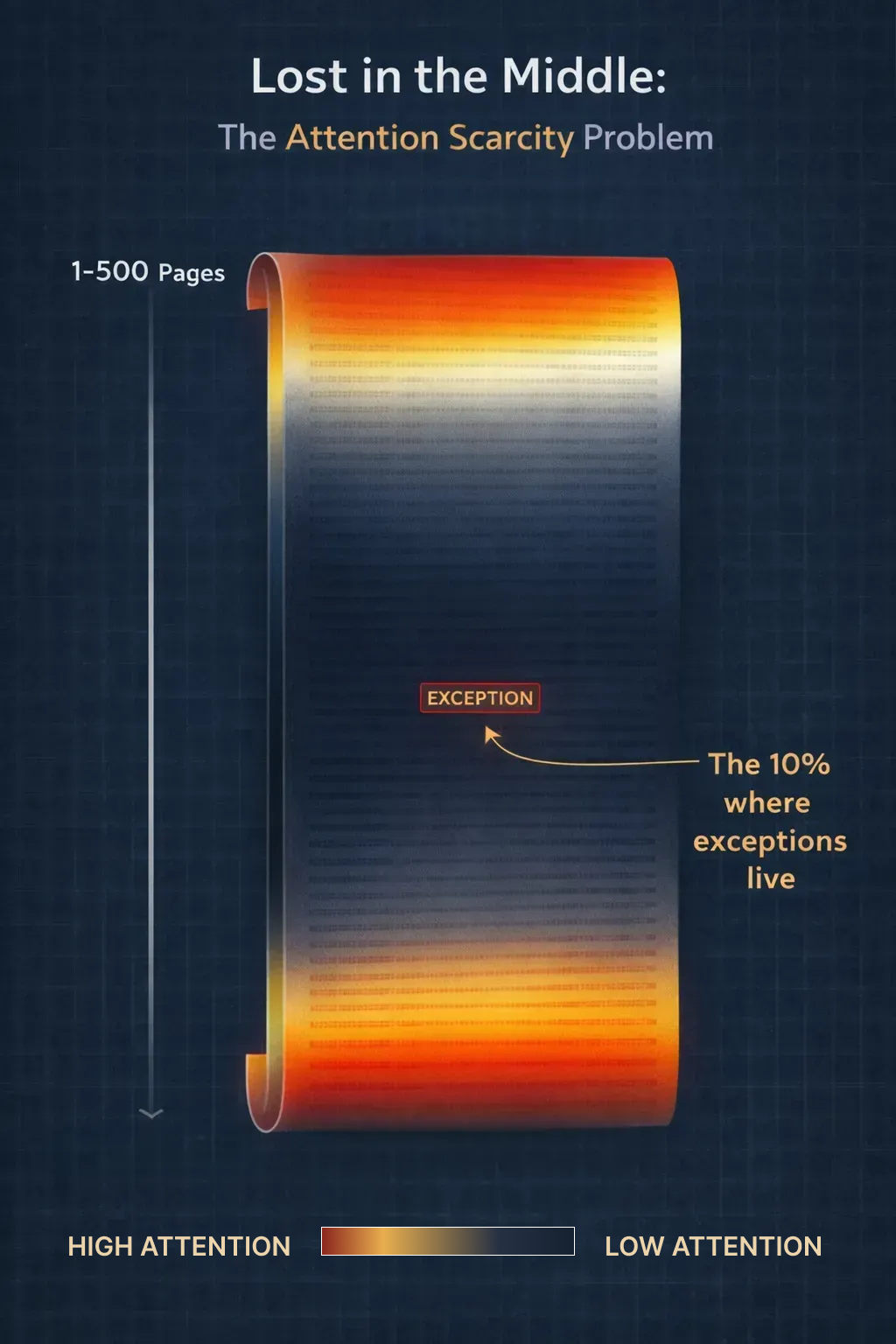

Not because it hallucinated. The correct answer was in the document. The model had technically "seen" it. But buried deep in the middle of a 500-page input, a narrow exception had simply failed to surface, a known failure mode that researchers have documented in detail. [1]

Anya’s mistake was not feeding the document to an LLM. Her mistake was assuming that “in context” meant “actually read.” In compliance, that gap between the two is not a minor inaccuracy. It is enforcement exposure. It is an audit risk. 90% is not good enough, [9] because the last 10% is precisely where exceptions live.

II. The realization: It’s not the model, it’s the context

Anya’s first instinct, like most engineers in this situation, was to blame the model. Maybe a better model would catch it. Maybe a better prompt would surface it. She spent a week testing both.

Neither fixed it reliably.

What she eventually understood, and what we have come to believe is the central insight of building compliance AI, is that the failure was not in the model’s intelligence. It was in the environment she had created for the model to reason inside. The model was doing exactly what models do: paying more attention to some parts of its input than others. She had just assumed it would pay attention to the right parts.

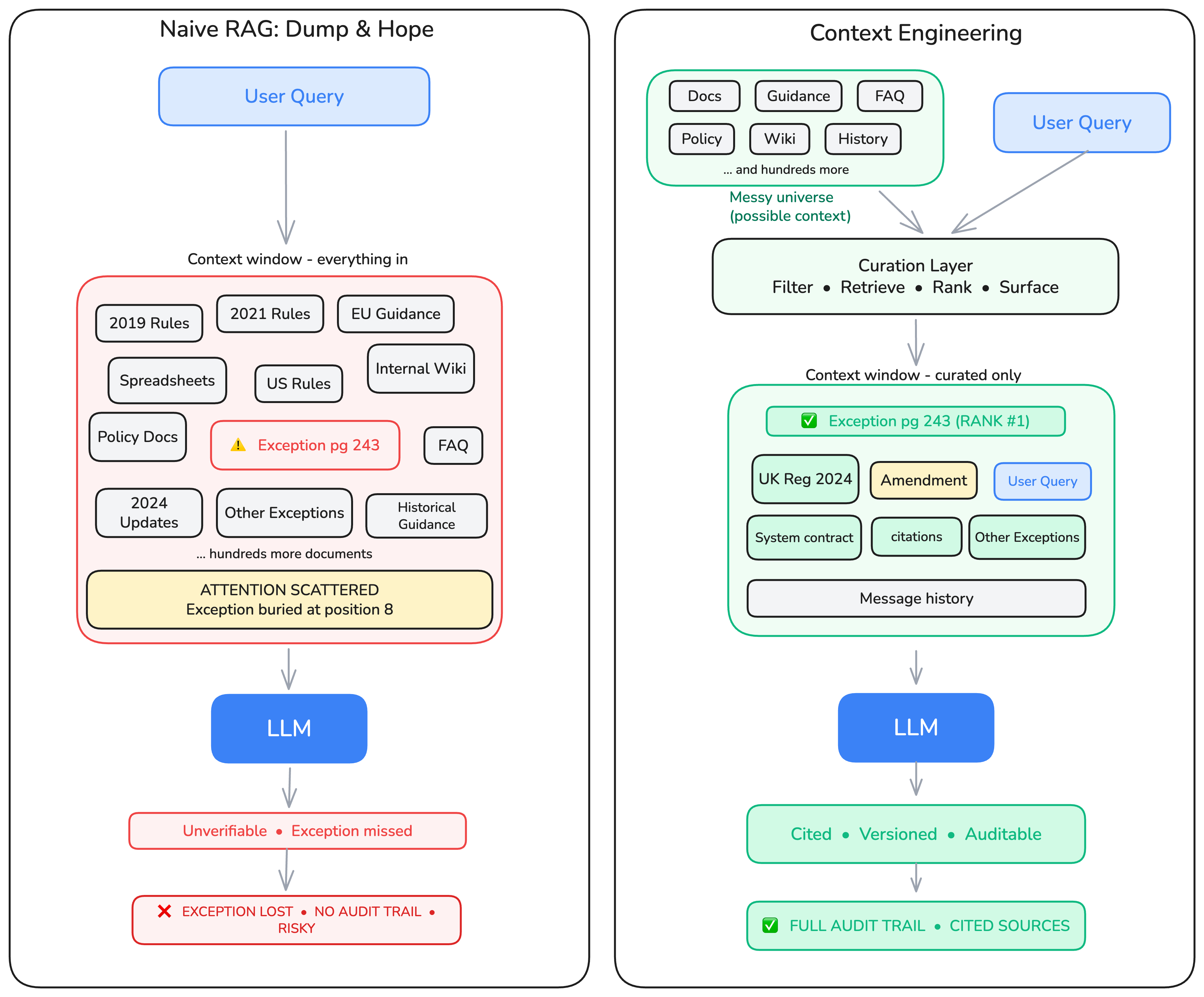

This is the difference between prompt engineering and context engineering. Prompt engineering is about the words you use to ask. Context engineering is about the environment you construct for the model to decide.

Anthropic defines context engineering as the set of strategies for curating and maintaining the optimal set of tokens during inference, everything that lands in the context window beyond the prompt itself. [3] LangChain frames it operationally: the discipline of filling the context window with exactly the right information at each step. [4]

In compliance, this framing matters enormously. What does "100%" actually mean here? It means decisions must be defensible, reasoning must be traceable to evidence, exceptions must be systematically surfaced, and unknowns must be escalated rather than guessed at. None of those properties come from a better prompt. They come from a better-engineered context.

“Giving a chef a recipe is prompt engineering. Designing the entire kitchen and sourcing the ingredients is context engineering.”

III. The struggle: How more context made things worse

Armed with this insight, Anya tried the logical next step: if context quality was the problem, surely more context would help. She expanded the input. She added adjacent regulatory documents, internal policy notes, and historical guidance. Her context window was enormous. Surely the answer was in there somewhere.

It got worse.

This is the counterintuitive trap at the heart of compliance AI, and it catches almost every team that builds in this space. Long context windows create the temptation to include everything and let the model sort it out. But a model under attention pressure does not sort it out fairly. It has structural biases that are particularly punishing in regulatory text.

Anthropic describes this as attention scarcity: every additional token competes for the model’s attention, diluting the signal. [3] Two specific failure modes emerge: evidence in the middle of a long context is less reliably used [1], and accuracy degrades as inputs grow longer even when the relevant evidence is present. [2]

The danger in compliance is that regulatory text makes exceptions easy to miss. Prominent general rules are easily retrieved, while crucial exceptions are brief, nested, and singular. Under pressure, a model will reliably favor the "loud" general rules over the correct exceptions.

We saw this produce three specific failure patterns:

- Lost in the Middle. The exception Anya needed was on page 243. That is precisely where it would be ignored. Research confirms LLMs consistently underweight evidence placed in the middle of long inputs. [1]

- Context Distraction. Adding ten years of regulatory history introduced noise that pulled the model toward older, outdated rules. The output became “generally” when the question required “if and only if.”

- Context Poisoning Across Turns. In longer agentic workflows, one mistaken assumption early in the chain contaminated every downstream check. The error was invisible until it surfaced in an output that was confidently, systematically wrong.

Anya had hit a wall. More model. More context. Both made it worse. She needed a different frame entirely.

IV. Engineering the goldilocks zone

The objective was not to provide more context, but better context. Rather than giving the model everything available, the aim became to provide only the information required, structured in the right order and at the right level of precision.

That question led us to a four-layer architecture. Each layer targets a specific failure mode from Section III.

Layer 1, The anchor: Keyword search (BM25)

The first layer is intentionally simple: keyword search using BM25. Regulatory language is highly precise, and many queries require exact citation matches. “MiFID II Annex I,” for example, is not something that can be loosely interpreted - it must be found exactly.

Semantic models, powerful as they are, tend to generalise. They might match “MiFID II Annex I” to “European financial regulation guidelines” and consider the job done. BM25 does not generalise. It finds the exact phrase or it does not find it. In compliance, that precision is the foundation everything else is built on. [6]

Layer 2, The bridge: semantic search

Keyword search alone cannot capture the linguistic variation found in regulatory texts. Semantic search fills this gap by retrieving conceptually related material (for example, matching “client protection” with “investor safeguards”). Together, keyword and semantic search produce a candidate set that is both precise and comprehensive.

Layer 3, The judge: reranking

The candidate set often contains both relevant passages and noise. A cross-encoder reranker evaluates each passage against the query and promotes the most relevant results before they reach the LLM. This filtering step ensures the model sees only the highest-relevance evidence. This is where the gap between 90% and 100% is actually closed. [5]

Layer 4, The scaffold: metadata and version control

Metadata filters determine which documents are eligible for retrieval in the first place, using tags such as jurisdiction, regulatory body, and effective date. Version control ensures the system retrieves the correct regulatory text for the relevant time period, returning the applicable rule rather than the most prominent one.

What happened when Anya ran her query through this pipeline

BM25 surfaced the exact statutory citation. Semantic search retrieved the related guidance notes. The cross-encoder promoted the one sub-clause, buried on page 243, that overrode the general rule. Metadata filtering ensured only the current effective version was in scope.

The exception appeared at the top of the context, rather than being buried in the document.

What this means for your compliance team

If you are a compliance officer reading this, here is the practical translation:

- Policy updates are applied surgically, only the affected chunks are re-indexed.

- Every output carries a citation trail to the exact source, version, and effective date.

- When evidence is insufficient, the system escalates rather than guesses.

- Any decision can be traced back to the specific clause that drove it.

V. The guardrails that make it enterprise-grade

Anya had a working pipeline. Then she showed it to her legal team. Their question was immediate: “Can you prove it?”

Not “does it get the right answer.” Prove it. Show us the source. Show us the version. Show us why it said what it said. Show us what it would have said if it did not know.

That conversation is where retrieval engineering ends and enterprise architecture begins. Three properties make the difference.

Data minimisation

Include only what the task requires. This is not just a GDPR principle (Article 5(1)(c), data adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary [7]). It is a retrieval quality principle. Irrelevant data is not neutral; it is noise that degrades attention and inflates legal risk simultaneously.

Traceability

Every output must cite the specific evidence snippets used, the source versions retrieved, and the decision path taken. This is what makes an AI output defensible rather than merely plausible. Without it, you have a model’s opinion. With it, you have an auditable record.

Refusal as a feature

A mature compliance system says “insufficient evidence” when evidence is insufficient. It says “jurisdiction unclear” when jurisdiction is unclear. This is not a limitation, it is the most important design decision in the system. A system that always answers is strictly more dangerous than one that sometimes refuses. Escalation is correctness.

VI. How you know it’s still working

Six months after deployment, Anya’s pipeline was handling hundreds of queries a week. The retrieval scores looked fine. But two regulatory amendments had come in, a corpus update had been pushed, and the reranking model had been swapped for a newer version. She had a nagging question: fine compared to what?

Standard LLM benchmarks do not answer that question. They test whether a model sounds right. Compliance requires testing whether a model is right, and can prove it. These are different problems.

The four evaluations that actually matter in this environment:

Exception Recall

The general rule is always retrieved, it’s prominent and well-represented. The exception is buried and appears once. Build a test set of questions where you know an exception exists, then measure whether the retrieved context contains the overriding clause, not just the general rule. A system scoring 95% on standard benchmarks can score below 60% here. That gap is where enforcement exposure lives.

Version Correctness

Ask the same question using document snapshots from before and after a regulatory amendment. The system should return different answers, citing the correct effective dates.

Refusal Correctness

Test cases where no reliable answer exists, sources conflict, or the query falls outside the system’s scope. The system should escalate rather than guess.

Contradiction Detection

Where older guidance conflicts with newer rules, the system should flag the conflict rather than produce a blended answer.

These checks are not a one-time launch exercise. They should run continuously whenever the corpus, models, or retrieval pipeline changes. Context engineering is not a one-off configuration - it is a discipline.

VII. Conclusion: Context is the moat

The last wave of applied genAI was about prompts. The next wave is about building agentic systems that can decide what to look up, what to trust, and what to ignore.

In compliance, this is not optional. A system that is “almost right” is not a slightly worse experience. It is a regulatory risk.

Three months after Anya’s pipeline went live, an external auditor came in with one request: walk us through how the system reached this conclusion.

Anya opened the decision trail, the exact clause retrieved, the effective date, and the evidence that supported the outcome. The auditor had no follow-up questions.

That is the bar. Not fluency. Evidence.

“If you can’t audit it, you can’t deploy it. Compliance AI is judged not by fluency but by evidence.”

About Zango

These are the principles underlying Zango’s work. Zango builds context-engineered compliance AI for banks and financial institutions. Our platform combines precision retrieval, time-aware regulatory corpora, and human-in-the-loop escalation to deliver outputs that are traceable, auditable, and built for regulated environments.

Join our team to build high-stakes, transformative compliance products using Enterprise AI. We leverage AI to solve complex regulatory challenges, boosting efficiency and accuracy for large organizations. Our Enterprise AI solutions ensure scalability, security, and integration. Apply at zango.ai/careers

References

- [1] Liu et al. (2023). Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts. arXiv: 2307. 03172.

- [2] Du et al. (2025). Context Length Alone Hurts LLM Performance Despite Perfect Retrieval. arXiv: 2510. 05381.

- [3] Anthropic (2025). Effective context engineering for AI agents. anthropic. com/engineering.

- [4] LangChain (n. d. ). Context engineering for agents. blog. langchain. dev.

- [5] Abdallah et al. (2025). How Good are LLM-based Rerankers? arXiv: 2508. 16757.

- [6] Robertson & Zaragoza (2009). The Probabilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond.

- [7] ICO UK (n. d. ). Principle (c): Data minimisation. ico. org. uk.

- [8] Zango (2024). Agentic splitting: our novel approach to chunking.

- [9] Zango (2025). Why 90% isn’t good enough in compliance AI.